Trade mark owners of marks, which are logos or devices, are well advised to ensure that they own copyright in the marks, which are artistic works for the purposes of copyright. This will mean that in the event of an alleged infringement of a mark, there is an additional potential cause of action for infringement of copyright, as well as trade mark infringement. This was partially successful for AGL in the matter of AGL Energy Limited v Greenpeace Australia Pacific Limited [2021] FCA 625.

The case involved consideration of some interesting issues in relation to both trade mark infringement and the use of trade marks and fair dealing defences for infringement of copyright.

The case

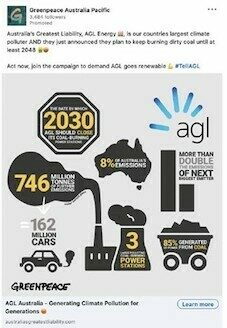

In late 2019, environmental activism organisation Greenpeace launched a campaign targeting Australian energy giant AGL, for what Greenpeace considered to be AGL’s poor environmental practices. The campaign incorporated AGL’s logo together with the tagline “Australia’s Greatest Liability” (pictured below). Greenpeace used this modified logo in online banner advertisements, street posters, photographs of placards, on social media, and on a website. Each of these uses displayed the modified logo together with taglines such as “Still Australia’s Biggest Climate Polluter” and “Generating Pollution For Generations”. Additionally, many of the advertisements drew attention and contained links to a detailed report commissioned by Greenpeace entitled “Coal-faced: Exposing AGL as Australia’s biggest climate polluter”.

AGL was, unsurprisingly, unhappy with the negative publicity and brought injunctive proceedings in the Federal Court to stop Greenpeace from using its logo. That application was unsuccessful. Predictably, and in yet another example of the “Streisand effect” (when an attempt to suppress information backfires), the litigation generated huge publicity and drew significant attention to the Greenpeace campaign. Despite the loss, AGL continued to fuel the media fire and proceeded to trial before Justice Burley of the Federal Court.

The issues in the case

AGL’s case was run on the premise that it did not seek to prevent Greenpeace from engaging in its campaign, but rather took issue with Greenpeace’s use of its logo. AGL sought to stop that use by alleging two contraventions:

- that the modified AGL logo is substantially identical to the AGL logo and infringed AGL’s registered trade mark; and

- that the modified AGL logo infringed AGL’s copyright in the logo.

The defences

Greenpeace denied infringing AGL’s copyright, stating that its use of the modified AGL logo amounts to fair dealing, which under Australian law allows copyrighted material to be used for the purpose of criticism or review or parody or satire.

Greenpeace also denied trade mark infringement on the basis that it had not used the modified AGL logo as a trade mark, that is, in relation to goods or services in respect of which the trade mark was registered.

The findings/trade mark use

AGL holds a registered trade mark for its logo. The Court had to consider whether Greenpeace’s incorporation of the AGL logo in its campaign constituted a “use” of that trade mark for the purpose of the Trade Marks Act. This involved consideration of whether in the manner in which the modified logo was used by Greenpeace, it would appear to consumers that the logo was being used by Greenpeace:

- to promote or associate any goods or services for which AGLs logo was registered,

- so as to indicate a connection in the course of trade between those services and Greenpeace.

Burley J found that consumers would not perceive Greenpeace to be promoting or associating any goods or services by reference to the trade mark. He held that rather, Greenpeace had used the modified AGL logo specifically to refer to AGL and the goods and services that AGL provides.

On that basis, AGL failed in its trade mark infringement claim.

Copyright infringement/fair dealing

There was no dispute between the parties that AGL owned copyright in its logo or that the modified logo was a reproduction of the logo. Greenpeace instead fought the allegation of an infringement by relying on the defence of fair dealing under s 41A of the Copyright Act. In order to make out its defence, Greenpeace had to establish, first, that there was “fair dealing” with AGL’s logo and, secondly, that the dealing was for the purpose of parody or satire.

Fair dealing is a notoriously elusive concept that is highly dependent on the circumstances of the case. For example, it has been described variously as:

- “depend[ant] on the nature of the work, the character of the impugned dealing, and the particular fair dealing purpose invoked”; and

- “a question of degree ... or of fact and impression ...”.[1]

Put simply, at least one purpose of Greenpeace’s use of the AGL logo must have been parody or satire, and that use must be genuine.

Burley J accepted that Greenpeace’s intention was to draw public attention to and to promote public debate about AGL’s conduct. This was achieved through a satirical message and was not for a commercial purpose. This was held to constitute fair dealing.

Burley J decided that because of the overlap in the concepts, it was unnecessary to distinguish between parody and satire for the purposes of the defence. His Honour held that the ridicule potent in the message of the modified AGL logo is likely to be immediately perceived and that many would see these uses as darkly humorous because the combined effect is ridiculous. It was also found that because the words “Presented by Greenpeace” were positioned closely to the modified AGL logo, anyone reading the message would understand that AGL would not be calling itself “Australia’s Greatest Liability” and that the message came from Greenpeace.

The Court rejected AGL’s submission that because Greenpeace seeks to bring about change by its media campaign, that must be considered to be its true purpose. Burley J held that the purpose of parody or satire is frequently to attract the attention of viewers and draw to their attention an object of criticism or ridicule, holding that the satire or parody was not supplanted by a disqualifying ulterior motive.

Additionally, the Court held for the purpose of the fair use defence, there is no need for the parody or satire to be directed towards the artistic work itself.

Criticism or review/Facebook and LinkedIn

However, it was not a total landslide for Greenpeace; Burley J found that the use of the AGL logo in the Instagram, Facebook and LinkedIn posts (pictured below) would not be perceived to have the characteristics of parody or satire.

Greenpeace contended that these social media posts could not constitute a breach of copyright because they were for the purpose of criticism or review within the meaning of section 41 of the Copyright Act. These arguments failed.

The three key principles for determining whether something constitutes criticism or review are as follows:[2]

- Criticism and review are words of wide and indefinite scope which should be interpreted liberally; nevertheless, criticism and review involve the passing of judgment; criticism and review may be strongly expressed;

- Criticism and review must be genuine and not a pretence for some other form of purpose, but if genuine, need not necessarily be balanced;

- Criticism and review extend to thoughts underlying the expression of the copyright works or subject matter.

With these principles in mind, Burley J considered the Instagram and Facebook posts, finding that they did not possess the character of critical comment or judgment of a work. He held that the images did not rise above the level of protest statements that are critical of AGL as a company, and would not be understood to represent criticism of review, whether of the AGL logo or any other work. His Honour found further that the commentary accompanying the posts did not sufficiently qualify the image to influence this view.

Burley J was more sympathetic to the LinkedIn post, which he said “perhaps comes closer to amounting to criticism or review”. His Honour found that the facts and figures relating to the conduct of AGL that were the subject of the criticism are clearly set out in that post together with language such as “More than DOUBLE the emissions OF NEXT biggest emitter”, which makes plain that the criticism is of the underlying conduct of AGL. However, His Honour went on to say that it is not apparent from this post that it “was for the purpose of criticising or reviewing AGL’s greenwashing materials, particularly because there is no reference to those materials in the post. Indeed, it is not apparent that it represents criticism of any work, whether the AGL logo or otherwise. I am not satisfied that Greenpeace has made out the defence in relation to this post”.

Conclusion

Ultimately, Burley J only granted injunctive relief restraining Greenpeace from using the modified logo with respect to the LinkedIn, Facebook and Instagram posts, but otherwise dismissed the proceedings and refused to order AGL costs.

While this appears to be, overall, a victory for Greenpeace, there are substantial implications which stem from the way the Court interpreted the fair use defence of review or criticism. The Court found that statements of fact (for example: “AGL is Australia’s biggest climate polluter”) were not sufficient to constitute criticism, as the criticism must pass judgment and, in doing so, “rise above the level of protest statements that are critical of AGL as a company”.

Organisations and individuals seeking to protest must be careful that they meet this high threshold, particularly when posting on social media.

Pro Sieben AG v Carlton UK Television Ltd [1999] 1 WLR 605 (Robert Walker LJ at 613, Henry and Nourse LLJ agreeing at 619

TCN Channel Nine Pty Ltd v Network Ten Pty Ltd [2001] FCA 108, per Conti J at [66]